Does welfare for workers subsidize Walmart?

Matthew Martin

4/16/2015 09:36:00 AM

Tweetable

At one level, I think most proponents of this argument are making a values claim and not a causal one. Compared to the counter-factual where Walmart and others paid enough so that none of their employees qualified for public assistance, these companies are the beneficiaries of huge public subsidies. That's not the same as arguing that simply repealing welfare would be enough to cause these employers to pay that much. The general sense is that Walmart and others could pay all their workers enough:

At over $446 billion per year, Walmart is the third highest revenue grossing corporation in the world. Walmart earns over $15 billion per year in pure profit and pays its executives handsomely. In 2011, Walmart CEO Mike Duke – already a millionaire a dozen times over – received an $18.1 million compensation package. The Walton family controlling over 48 percent of the corporation through stock ownership does even better. Together, members of the Walton family are worth in excess of $102 billion – which makes them one of the richest families in the world.not necessarily that they would in a world without public subsidies:

Meanwhile, Walmart routinely blocks any attempt by workers to organize, using anti-union propaganda and scare tactics, firing employees without just cause, failing to provide any form of decent healthcare coverage or a livable wage.See the difference?

To make matters worse, these abusive Walmart policies have increased employee reliance on government assistance and the need for a government funded social safety net. In fact, Walmart has become the number one driver behind the growing use of food stamps in the United States with "as many as 80 percent of workers in Wal-Mart stores using food stamps."

To be sure, I don't buy the values argument here. Yes, society does have a moral obligation to both ensure that everyone earns more than subsistence and to share prosperity as broadly as possible. Sometimes it may be more economically efficient to do this through policies that affect wages than through government-budgeted redistribution (though I will scrutinize your model if you make this claim), but I see no inherent moral reason to prefer redistribution through the market wage mechanism. Low wages supplemented by welfare is perfectly moral policy for low-skill workers, and the argument that Walmart is shamefully exploiting the welfare system only plays into the right-wing narrative that welfare is shameful and low-skill workers are icky. The left-wing attempt to vilify Walmart for hiring low-productivity workers only further vilifies low-productivity workers.

But then, not all proponents of the welfare-for-walmart theory are sticking to the values claim. Some go further to make the causal claim that reducing welfare benefits would cause employers to increase wages:

@UpdatedPriors It seems reasonable and important to inquire as to whether wages are being suppressed by public assistance.

— Binyamin Appelbaum (@BCAppelbaum) April 13, 2015So, if that's the hypothesis, what's the model? I think this is the model most proponents have in mind:

@ModeledBehavior @hyperplanes workers must be paid at least enough to live. Without govt assistant many low income workers would starve

— M the Merciless (@MPAVictoria) April 16, 2015

So, that's the theory anyway. I'm not sure it's even internally consistent--more workers alive would increase labor supply, that's true, but it also increases the demand for goods and services. In the standard DSGE model, for example, an increase in the labor supply will eventually (pretty rapidly, actually) cause the capital stock to increase by just enough to maintain the original wage rate. So without some behind-the-scenes theory for why public welfare decreases the capital/labor ratio (distortionary taxation?) this theory doesn't add up.1

There are variants of the labor supply story that don't assume mass starvation:

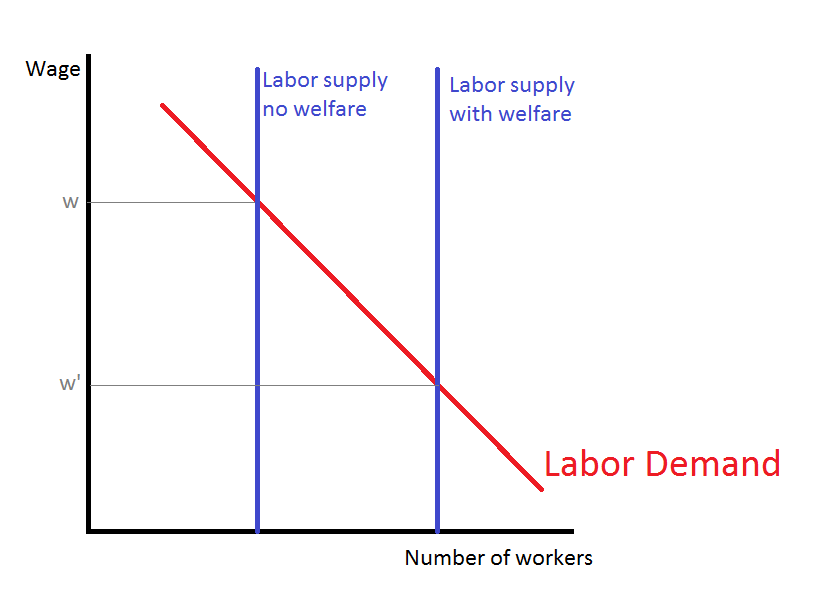

@ModeledBehavior @hyperplanes SNAP should raise reservation wages, while EITC opposite. Would be true in large class of models.

— Arindrajit Dube (@arindube) April 16, 20151. To see why I make this claim, consider the DSGE model I posted previously. (I'm posting math as images with white text--if your using an RSS feed with a white background, click over here) The consumption Euler equation without distortionary taxation is

, while from the firm's profit-maximization problem

, while from the firm's profit-maximization problem  . That means the steady state labor/capital ratio,

. That means the steady state labor/capital ratio,  , is fixed by technology, time preferences, and capital depreciation. Also from the firm's problem,

, is fixed by technology, time preferences, and capital depreciation. Also from the firm's problem,  , with fixed L/K implies increasing labor supply does not decrease wages, except in the short-run transition phase. No doubt there are a variety of deviations from the standard model that would allow long-run wages to change, but, as always, if you don't present your model it didn't happen. We can't debate claims that aren't stated.

, with fixed L/K implies increasing labor supply does not decrease wages, except in the short-run transition phase. No doubt there are a variety of deviations from the standard model that would allow long-run wages to change, but, as always, if you don't present your model it didn't happen. We can't debate claims that aren't stated.