Why we have no idea if ACA premiums are rising

Matthew Martin

9/14/2014 03:13:00 PM

Tweetable

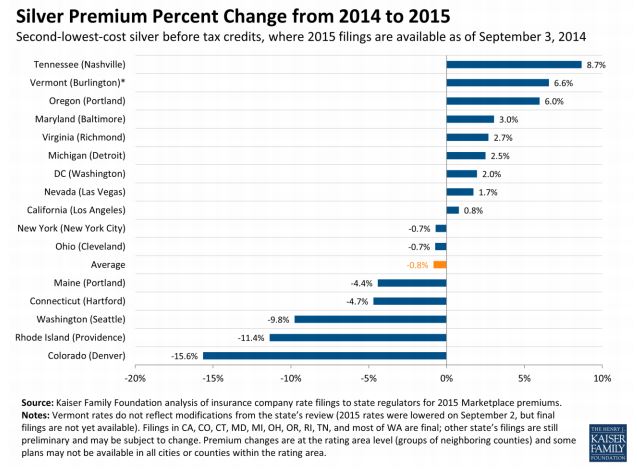

The Kaiser study compared the second-lowest-cost silver plans on the exchanges for 16 cities from 2014 and 2015, finding an average decrease of 0.8 percent from 2014 to 2015. I do have doubts about the dataset itself--it's possible that states that offer more comprehensive data (the criteria for inclusion in this study) are not representative of most states. Time will tell.

But Avik Roy isn't impressed: he cites this McKinsey study finding an 8 percent increase on average between 2014 and 2015. Their methods are similar to Kaiser's, with (as far as I can tell) the only major difference[update] being that McKinsey looked at the cheapest silver plan while Kaiser had looked at the second-cheapest plan (same caveats about incomplete data apply to both). That tells me that estimators of this type aren't very stable, and thus not very useful.

These estimators suffer from compositional fallacies. For example, on twitter Austin Frakt makes an excellent observation:

Empl-sponsored health ins premium growth moderating but cost-sharing rising. Controlling for plan generosity, what's the real growth rate?

— Austin Frakt (@afrakt) September 10, 2014When I think about premium hikes here’s the “ideal” estimator I have in mind: take the premium for each specific plan in 2015 and subtract the 2014 premium for the exact same plan, and then take the average of the differences weighted by the number of 2014 buyers for each plan. This truly tells us the average—not the mostly meaningless “benchmark”—change in premiums while eliminating all confounding compositional effects. It’s also mostly impossible, because the plans offered in 2015 are not the same as the ones in 2014. They never are. Still, I think this is the standard against which various metrics should be compared—a statistic is only valid if it approximates this. Kaiser and McKinsey haven’t got it.

[update] Avik Roy also pointed out this difference in methods between the two studies:

@hyperplanes Kaiser study only looked at cities. That’s useful, but not nationally representative. PwC/McKinsey better for that.

— Avik Roy (@Avik) September 14, 2014